The Business of Production Music

by: Art Phillips

first Published in

‘Loud Mouth’ (Music Trust E-zine)

April 2019

CONTENTS

What is production music?

Why use production music rather than specifically scored commissioned music?

A history of production music

Under the radar, it’s a pretty big industry

An insider’s view of how it all works

The music

Metadata

Marketing

The money

What is production music?

When we think of music composition we usually think of the great classical composers such as Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, or the contemporary writers such as Lennon & McCartney, Dylan, Bacharach, Elton John, or we readily recall the great music scores from those famous feature films and television series that took us on a memorable emotional journey.

These music creatives and their recordings have become embedded in our music culture, but production music does not generally receive any public attention as it flies under the radar. The majority of people don’t even know it exists as production music is not usually for sale commercially to the general public.

Since the early 1900’s with the early silent films, stock music was utilized to provide a desired mood to accompany the message coming from the screen. Production music, which was once called stock mood music, cue music, cinema music or library music is an important source for finding a suitable soundtrack to enhance storytelling.

Production music libraries are well-curated catalogues of music that provide a high quality and cost effective solution for music licensing. The music from these catalogues is diverse, and is search user-friendly with the use of creative metadata that aligns to emotional keywords and descriptions, packaged neatly online and covers a multitude of musical styles and genres.

It is composed, produced and recorded specifically for the synchronization or dubbing in audio and audiovisual productions, which can include but is not limited to advertising campaigns, feature films, documentaries, television series, DVD’S, radio programs, websites, online games, music on hold and ringtones.

‘Library (production music) was intended to extract the mood from all sorts of music, and sometimes it seems to capture the feel of an era better than the music which was actually sold at the time. If you want to find that strange (different) ingredient which makes modern music modern, futuristic library music isn’t a bad place to look’ (Trunk 2005, p. 6).

APRA AMCOS offers production music licensing for Australia and New Zealand with over hundreds of thousands of production music tracks across all musical styles. Licenses issued cover the right to reproduce both the musical work and the sound recording under one license umbrella. Other performance right organizations (PROs) around the globe and production music agents also offer licensing in their particular territories.

Locally, under APRA AMCOS jurisdiction, production music rates are reviewed and set annually. An example from the current 2019 Production Music Rate Card; for a 30 second usage (one unit) on national free to air television the license fee is $47.30. For Australian and New Zealand territories it’s $57.20, and for world clearance it is set at $ 235.40 per unit (30 seconds of music). The pay television rate is slightly lower, and the combination of free to air and pay television is $67.10 (national) per unit, $95.70 (Australia and New Zealand) and $359.70 (the world). For all media clearance, for the world, the rate is set at $702.90 per unit (30 seconds of use).

The rates for other mediums such as advertising, corporate video content, gaming and mobile apps are all published in the rate card:

‘http://apraamcos.com.au/media/customers/2019-PM-Rate-Card_AU.pdf’ (APRA AMCOS Production Music Rate Card 2019).

Why use production music rather than specifically scored commissioned music?

Commissioning music is generally much more expensive, there is the difficulty of getting the music straight away as it takes time to compose, produce and deliver. The pros of commissioned music are that the music is exclusive to the program or film and therefore no-one else has the ability to use that commissioned music score, it is custom made and written specifically from the heart for the intended scene of that production, and is therefore a unique signature to that program or film. The pros of production music are that the music already exists and is easy to find, there are a multitude of choices, with a quick one step mechanism to obtain a license to clear the music, and it is generally less expensive opposed to commissioned music.

Commissioned music is a collaboration between composer and filmmaker, whilst production music is a collaboration between the music supervisor, film editor or producer and the production music agent who helps them locate a suitable piece of existing (stock) music from the various music libraries available in the marketplace – and there are millions and millions of choices. However, it must be realized that production music is non-exclusive when licensed, meaning other programs or films can also use the same music.

There are pros and cons of each, and it really depends on the practical needs of the production itself, as each serve a viable purpose to supply an intended journey of emotions to enhance storytelling.

The history of production music

This is a fascinating chapter in 20th-century popular culture – so, where, how and why did it all begin?

In 1909, Meyer deWolfe, graduate of the Dutch Royal Conservatoire of Music, immigrated to London to work as a musical director, composer, musician, arranger and conductor with Provincial Cinematograph Theatres Limited. He established ‘deWolfe Music’, a sheet music library and was responsible for selecting the accompaniment to movies at a time when soundtracks were simply printed as music manuscripts and played live by musicians sitting inside the late-Edwardian Cinemas, Kinematograph theatres as they were also known. Meyer personally selected music from his library for many early silent film epics. He acted like a music supervisor as he assembled musical selections for the musicians to accompany the film.

Also in 1909, Thomas Edison Films included printed musical cue sheets of ‘suggestions for music’ that accompanied the delivery of their films for theatrical projection.

In 1913, Sam Fox Publishing of Cleveland Ohio began its long involvement in supplying library music in the form of sheet music folio books of ‘motion picture music’, where this music was mostly composed by John S. Zamecnik.

In 1919, the sheet music library ‘Kinothek’ from Berlin Germany, began publishing music folios to aid silent film accompanists.

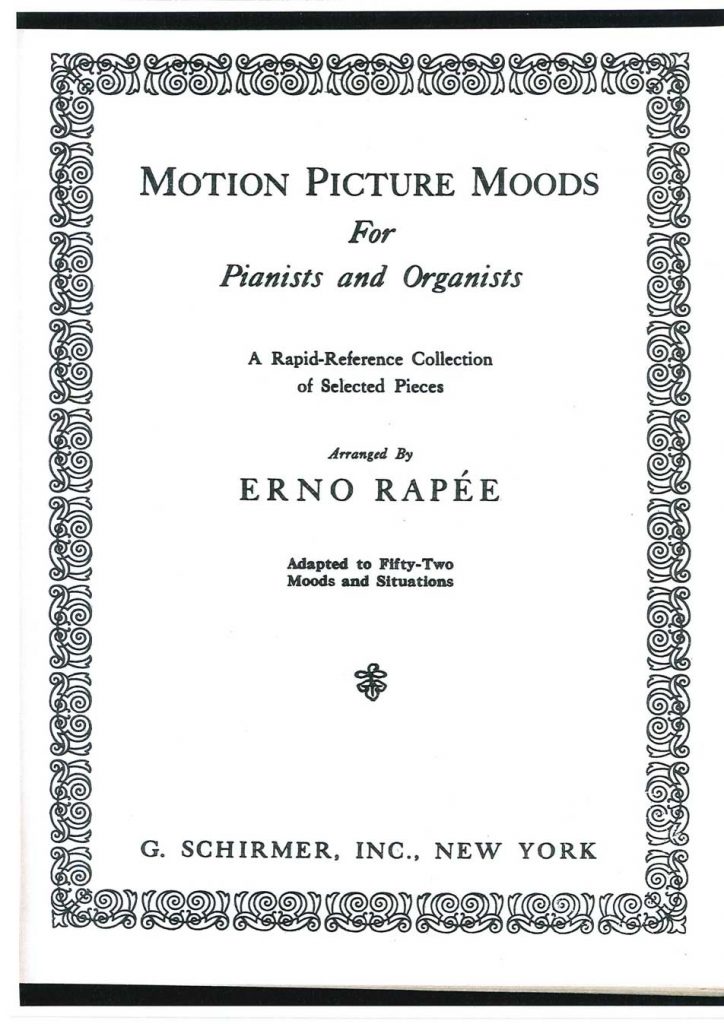

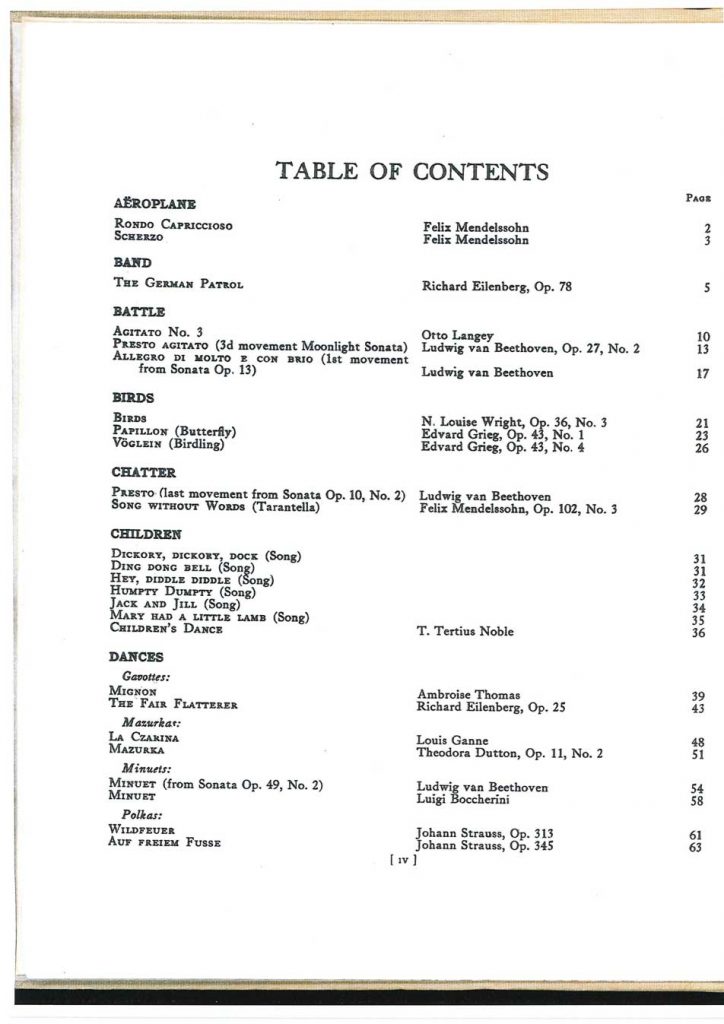

In 1924, G. Schirmer Inc., New York, published ‘Motion Picture Mood for Pianists and Organists’, a rapid-reference collection of selected works from classical repertoire, various folk style music as well as anthems and hymns from over thirty countries, assembled and arranged by Erno Rapee, a prolific silent film music composer who adapted existing tunes with references to fifty-two moods and storyline situations from battle music to chase, music for kids, hunting music, gruesome to sinister, western to religious, romantic to sadness, and many more moods and emotions.

As Rapee notes, ‘only one-third of all film footage depicts action; another third is concentrated on psychological situations; and the remaining third of a film restricts itself to scenery to atmosphere’ (Rapee 1924).

I believe Rapee refers to the importance of music to cohesively aid all three aspects to help sway an intended feeling to the audience. As I continually preach to my composition students, music for me is a third dimension to the screen, not unlike an invisible charter in its own right in the story.

In 1927, ‘following the advent of sound in movies, deWolfe Music began recording with the sound-on-disc technique and sound-on-film onto 35mm nitrate film. This was the birth of recorded production music. This highly volatile medium being recorded on 35mm nitrate film stock had a tendency to disintegrate if not kept in the right conditions, it was even known to explode as the company discovered when a film which had deteriorated into a fine nitrate powder ignited and blew out its Wardour Street basement. To counteract this, much of the stored music was copied onto ¼” tape after its invention during the Second World War. This guaranteed the longevity of the recordings for that time and ensured that they could be re-used later in other productions. Indeed, as technologies have changed, many of the early compositions have come on quite a journey, transferring to vinyl from 1962, to CD from 1985 and currently existing digitally on hard drives and as downloadable digital files via the internet’ (deWolfe Music, online 2019).

In 1928, we see the production of a recorded music library called The Brunswick Record Company USA, releasing 495 discs on 10” and 12” formats at 78rpm. The discs were mostly standard classical compositions and popular songs of the day. Suggestion music cue sheets were produced in the package for use to accompany the films.

In 1929, The Columbia Gramophone Company of London published a recorded music catalogue of classical recordings inclusive of reference suggestions relating to mood and emotions for use as incidental music in a variety of storyline situations.

In 1937, Boosey & Hawkes began creating records of original music compositions which more closely reflected the needs of radio drama as well as film productions.

In 1941, Chappell Music Publishers, London, was created and became another one of the largest sources of recorded mood music.

In the late 1940s, Capitol Records, Hollywood, created Capitol Transcription Services, who supplied music for dramatic radio series. It was a predecessor to the Capitol Q Series Music Library and the Hi-Q Music Library that followed.

Also in the late 40s, deWolfe Music expanded into North America, where a partnership with two film editors from Paramount Pictures named Corelli and Jacobs laid the foundations for a new venture in the USA. The proliferation of television sets during the fifties also added a whole new market for the deWolfe music library, and with it a unique piece of television history.

Also in the late 40s, Thomas J. Valentino and Emil Ascher began representing European recorded music libraries as their sole distribution agents in the United States. Sometimes they changed the names of the library cues (retitling) so that broadcast uses could be more easily tracked by the US performing right agencies, BMI and ASCAP.

Today, retitling, meaning one song with many titles with multiple registrations, is not good practice due to the identical digital recognition fingerprints that will occur and therein causing difficulty of ownership.

‘Digital algorithms automatically detect each piece of music and (ideally) every performance will be tracked and paid without the hassle of cue sheets or the burden of physically watermarking every track. Most libraries consider fingerprinting to be a critical step towards improving the fairness and accuracy of PRO distributions. In addition to performance tracking, fingerprinting systems are also being increasingly used by libraries to monitor sync uses of their catalog and by broadcasters to automatically generate cue sheets. These scenarios present an obvious conundrum for retitled music: since their audio files are not unique, each detection can no longer be linked to a unique title record, making accurate performance identification virtually impossible. Clearly, the practice of retitling only serves to stymie these important initiatives and therefore runs counter to the best interests of the industry’ (Production Music Association, online 2019).

As we see, the art of music scoring (music to picture) began with a few lists of stock music assembled by orchestra leaders, theatre organists and pianists, usually of various classical pieces or other music in sheet music form to accompany scenes in silent films. It was generally a live in-person process that involved some awkward segues or even improvised sections, as musicians scrambled to turn pages of their well-worn musical folios of sheet music. And as from the late 20s, music was created as a recorded music format for synchronization and licensing to film or radio programs.

As the majority of production music never usually becomes a global or national hit song, sometimes the accidental hit does occur. As author Joseph Lanza quotes, ‘such as the signature line (tune) of a much-loved television program like the theme from Dragnet, which was once a music library tune, and the Chappell Recorded Music Library’s music track entitled Puffin’ Billy, composed by Edward White, that was used for the children’s favourite television show, Captain Kangaroo, that CBS used as the opening theme’ (Lanza 1994, p. 64 & 65).

Since these time periods, there are numerous other important music libraries that have value added to the mix in our industry’s history, such as KPM, Bruton Music, FirstCom Music, Atmosphere Music, Universal Production Music, Sonoton Music, Boosey & Hawkes, Cavendish, BMG Production Music, 5Alarm Music and many others.

Under the radar, it’s a pretty big industry

The Production Music Association (PMA) has placed a dollar value on the revenues generated by production music for the first time, citing it as a billion dollar a year industry. ‘Production music, which is heard in film, TV and video productions, is often hidden in plain sight. In 2017, the PMA estimated that production music generated revenue of at least $500 million a year in the USA alone, and $1 Billion a year globally, while also supporting tens of thousands of jobs’ (Taylor 2017). (Adam Taylor is the Chairman of the Production Music Association and the President of Associated Production Music (APM) in the USA).

‘With substantial economic, creative and technological impact, the production music community has evolved during the past 90 years to become a significant part of the entertainment landscape in its own right. Yet, the community has often not quite gotten the full respect or recognition it deserves, and has long been treated as the music industry’s step-child. Today, production music stands ready for its spotlight, and is poised for an even brighter future’ (Saba 2017).

The Production Music Association is the leading advocate and voice of the production music community. They are a non-profit organization with over 700 music publisher members, ranging from major labels to independent boutiques. Their mission is to elevate the unique value of production music and to ensure the viability of the production music industry now and into the future.

An insider’s view of how it all works

I have had many years of experience working in production music and so can describe in detail how the industry works. It’s information that is not easy to come by and I hope that it is of interest to you, the reader.

I have worked as a composer, musician (guitarist), arranger, orchestrator and producer for 45 years. Much of my career has been working as music composer and producer for the largest and most sought after production music companies around the world, where I’ve delivered over 60 production music albums as composer to labels such as Universal Production Music, FirstCom Music, Bruton Music, Chappell Recorded Music Library, One Music, Sonoton Music, 5Alarm Music, Boosey & Hawkes, Cavendish Music, OneMusic and Groovers Music Library (Japan). (www.artphillips.com)

Just six years ago, I decided to branch out and create my own production music library, 101 Music Pty Ltd, where I currently have 42 albums in the 101 Music catalogue. (www.101.audio)

The market is faced with a multitude of challenges in this day and age, such as depleting license fees for all sorts of reasons including the repercussions from many disruptive models, the saturation and glut of new music coming into the marketplace on a weekly basis, the amount of new program delivery systems such as Netflix, Stan and the like, and the catch-up from copyright collection societies and agencies to be able to sustain what once ‘was’ and now ‘is’ with these new on-demand non-broadcast program models. As more and more people use the on-demand services to view television and film programs, we are in a continual catch-up game with respect to copyright collecting and practical royalty distributions from license and performance fees. It’s certainly a brave new world out there for our industry.

101 Music Pty Ltd is based in Sydney Australia and has representation in over 80 countries under 25 separate contractual agreements. These agreements are party with music sub-publisher agents who specialize in the representation of many production music catalogues. The sub-publishers market this music to clients in their specific territories. Their clients include television networks, independent production companies, film houses, advertising agencies, internet content providers and the like. The agreements between 101 Music Pty Ltd and the sub-publisher are generally a 3-year term with automatic one year renewals.

101 Music has no in-house staff, but outsources numerous duties as required to specialized independent contractors. My company provides quite a bit of work for many creatives both here and abroad, which is a joy for me to be able to be doing at this stage in my career, such as musicians, music composers and producers, audio engineers, creative metadata assistants, artwork designers, marketing experts, website creators and music delivery companies who deliver my releases globally to all my sub-publisher agents. Generally, 101 Music Pty Ltd release ten albums per year where I usually compose three of those myself and outsource the other seven to local and overseas composers who I know can deliver effectively and efficiently. My days are full overseeing their work, executive producing their incoming product, composing myself for the label, planning the marketing scope for the upcoming release, and designing the next set of releases for the following year.

101 Music Pty Ltd is a small and boutique production music label with 42 album releases in its portfolio, that’s some 500-original musical composition titles; and is providing a wonderful vehicle for myself and many other industry creatives.

The business model is moulded around a four-step attribute and thought process, all of equal importance with the first three requiring creativity and innovation. They are music, metadata, marketing and money.

The music

The music product and creative approach to writing production music is slightly different than scoring music to picture. It is also a bit different than writing pop songs or any other type of music. However, as all music, production music must have strong appeal, aligning to an emotional purpose and to move the listener in a purposeful direction. Most importantly, the music must be cohesive to its track description and track keywords in the metadata spreadsheet with the ability to take the listener on an emotional journey aligned to the keyword adjectives. These keywords and track descriptions should tell the story about the music and define where it might best get used. The music should have stand-alone appeal as a musical work in itself to hold interest as an audio file, to include musical hooks whether subtle or obvious along the piece, and have the ability to work to a multitude of storytelling possibilities with many cutting points for strong screen editor appeal.

The music must consistently build and layer with musical textures and thematic parts as it unfolds section by section, and it needs to capture sonic and emotional intrigue. The audio must be clean state-of-the-art sound files and mastered at consistent levels across the entire production music catalogue. Maintaining consistency of quality is critical for success.

It is most important to utilize composers who know how to write and deliver this type of music, which includes strong skill sets in orchestration and arranging techniques and innovative music production abilities. I believe it is also essential to have the final product mixed and mastered by an audio expert rather than accepting a music composers mix. Saving costs never does justice to the end result, nor to sustainability or longevity in the marketplace.

The 101 Music album projects are all individually geared toward a specific direction, with an intended usage forecast. The catalogue is quite diverse including projects that range from ethereal acoustic landscape albums, light comic, positive, fun and happy advertising scores, all sorts of television drama, corporate style soundtracks, pop instrumental and vocals to epic cinematic film trailer scores. Each album released consists of 12 main track titles. Each of these copyright titles are delivered with alternate versions. The main track version is generally a 2:15 ~ 3:00 duration, a :30 second version for advertising, sometimes a :60 version, possibly a :15 second version, an underscore version or two of the main as well as the advertising underscore version cut downs (underscore = having no thematic melody, which works well under dialogue), and a couple short sting versions of a few seconds duration each. This gives the client/user various options which can be extremely important for their visual and emotional storyline requirements. In addition, deliveries with these alternate track options gives the catalogue a more stable and sustainable ground for success, supplying a much wider scope for use.

Some libraries deliver stems of each track title. Stems are individual mix-outs of various sections of the musical ensemble or orchestra. I do this at times when I am commissioned from certain outside libraries, as I continually take one or two outside commissions per year for some of the major labels. However, my approach with 101 Music Pty Ltd is that I do not supply stems with my deliveries, and, so far no-one has ever asked. My reasoning is, the users could destroy the music by mixing together elements that just don’t work (to me anyway), or they could combine my stems with another library’s stems and create copyright havoc or some atonal nonsense. It would also be inaccurate to expect correct audio fingerprinting on such stem files.

Nevertheless, as I do provide practical alternative mixes and versions, I believe this is sufficient to purpose, and not having additional mix-outs stems keeps my production costs and deliveries much more practical.

The brief given to my music composers, or to myself as composer, is the very first step in launching the creative production process which can take anywhere up to twelve months to achieve for a final delivery, sometimes as little as two and a half months. 101 Music has at least 3 projects on the production line at a given time.

Before beginning any project, I devise a shortlist of work in progress ‘keywords’ for the album and more precise keywords for each individual track, as well as a rough ‘track descriptions’ and an ‘album description’ to help guide the emotional content and creative path.

My composers work one track at a time for delivery, where as executive producer, I help sculpt the production along the way, and sometimes the arrangements when needed. Usually there might be one or two slight changes I request along the work trail for the main, then we concentrate on the alternative versions, with the same process to ensure they are all working well. The trick is usually getting the track to build nicely to hold interest and to end suitably for production music. End fades do not work at all, as strong endings are best suited in production music. The underscores are fairly straight forward to construct by pulling all melodic parts and counter melodies out of the file. Sometimes when delivering underscore A, B or C it becomes a bit tricky to work out what to omit to create a workable version.

It is essential that the 30s are exact time duration, being certain that the last musical hit occurs around :28 seconds generally, but not much earlier nor much later in order to allow reverb trail to provide the opportunity for a :29 pull-down for the user if needed for a television ad. The sting versions consist of the last big moment of the piece, such as the last :08 ~ :12 seconds of the tail-end conclusion of music from the main.

I ensure each album project has more than just one live musician, and that it is never totally electronic, no matter what the genre. Being organic and green is good!

The track order of the album release is also a very important factor, as the flow of the album story is essential to hold continual interest, especially if clients might be auditioning the project from head to tail which sometimes does happen. Some clients may not listen in that fashion, as they are just keyword searching and finding, but I believe it needs to be an audiophile that is presented as a commercial album release.

As Elias Leight quotes in a recent Rolling Stone Magazine article about why track sequencing in an album matters more than ever in the age of streaming, ‘In theory, front-loading an album (best tracks at top for the running order) has an attention-holding effect. If people don’t appreciate the top of the album, they won’t even get to the bottom of it, but there’s also a psychological aspect to it’ (Lewis 2019).

As Barry Hefner Johnson, manager of 21 Savage says, ‘I’ve had a million and one conversations about the whole album sequencing thing. This really affects new and younger artists that are trying to capture the attention of an audience. If you don’t, they’re gonna move on to something else too quick. Put the best six songs up front, make it top-heavy to keep ’em glued in for a longer listen. If you can make it past the first six songs, people almost deem your album a classic’ (Johnson 2019).

As Henny Yegezu, who manages Goldlink and Smino says, ‘Playlist-listening is already out-performing album-listening in surveys, so people are positioning their albums to feel like playlists. Think of a Spotify or Apple playlist: Positioning matters. The number one song on the playlist is something you’re gunning for. The way you gauge success is how far up and down you are’ (Yegezu 2019).

Metadata

In addition to the music product itself, 101 Music creates and delivers extensive metadata in an Excel spreadsheet, which forms a part of the audio files and deliveries.

The metadata consists of creative ‘wordsmithing’, i.e. appropriate album and track titles that coincide with the music feel, album and track keywords, album and track descriptions, name of instruments used on each track version, tempo / beats per minute, musical key as well as data relating to the identity of the music composer and music publisher such as their affiliation to a PRO (performing right organization), and their membership IPI number, an international standard number that every composer and music publisher receives as it identifies them globally to ensure income is attributed correctly. It is also essential to assign and digitally stamp an ISRC code to every audio file.

The metadata is critical and needs to be meticulously created as this data is how music is searched and ultimately found. The keywords and point of sale descriptions associated with the metadata are also the launching pad for marketing.

Creating the excel spreadsheet file of metadata for each release, some 75 or so columns and some 84 rows of data, can take up to a couple weeks to produce effectively. It is a requirement for my sub-publishing deals and is essential in order to successfully obtain music copyright licenses, e.g. usages of that music. And of course, the copyright details and IPI identifying numbers are essential for royalty distributions to be attributed to the correct copyright holders.

I have a metadata assistant working from South Carolina in the USA who is brilliant at helping to devise interesting and creative metadata.

101 delivers all its product to its sub-publishers via two delivery methods which are very efficient, Harvest Media Distribution and also SourceAudio. This means that once I load a new release into the Harvest Media and SourceAudio systems, which include all audio files, the metadata file, the album artwork and all the marketing material, that each of my 24 sub-publisher agents across the globe are immediately informed of its release and can download straight into their online distribution site ready for their clients to see and license, and most do this generally within 48 hours of a release. I treasure this as I have always believed there is no time-wasting allowed in business if you are a serious player.

Marketing

Marketing is essential for the brand and for each specific album release. Once an album is released into the marketplace it usually takes 18 to 24 months to realize the data available to analyze results.

For 101 Music, it all begins with an album title once the music is set in place. The album release title is critical as it drives the packaging and then gives rise to the marketing concepts. The album title needs to supply an emotional feel and a hint to a description and imagery.

The album artwork design then begins to be considered. The image should identify the emotional genre, style and feel of the music. Even though albums are not physically released in CD form, the digital image artwork is essential as a focal point to help define the album project release. I work with an Australian art director who has had a renowned background in advertising and marketing.

Here’s a link to a recent release entitled Turning Corners 101M041, composed by Gareth James Hudson for 101 Music Pty Ltd,

with the album description: Upbeat, urban, confident, corporate. Catchy, feel-good, positive and radio-friendly rhythmic pop instrumental tunes for business, banking, stock reports, advertising, well-being and contemporary fashion, and using these album keywords: uplifting, positive, confident, assuring, optimistic, joyful, happy, upbeat, feel-good, anthemic, rousing, moving, achieving, excellence, success, winning, well-being, business, fashion, community, lifestyle, teamwork, urban, advertising, corporate.

In addition to the importance of the music, it’s all about catchy adjectives and a hook style description.

Other 101 Music releases can be found at https://101.audio/releases

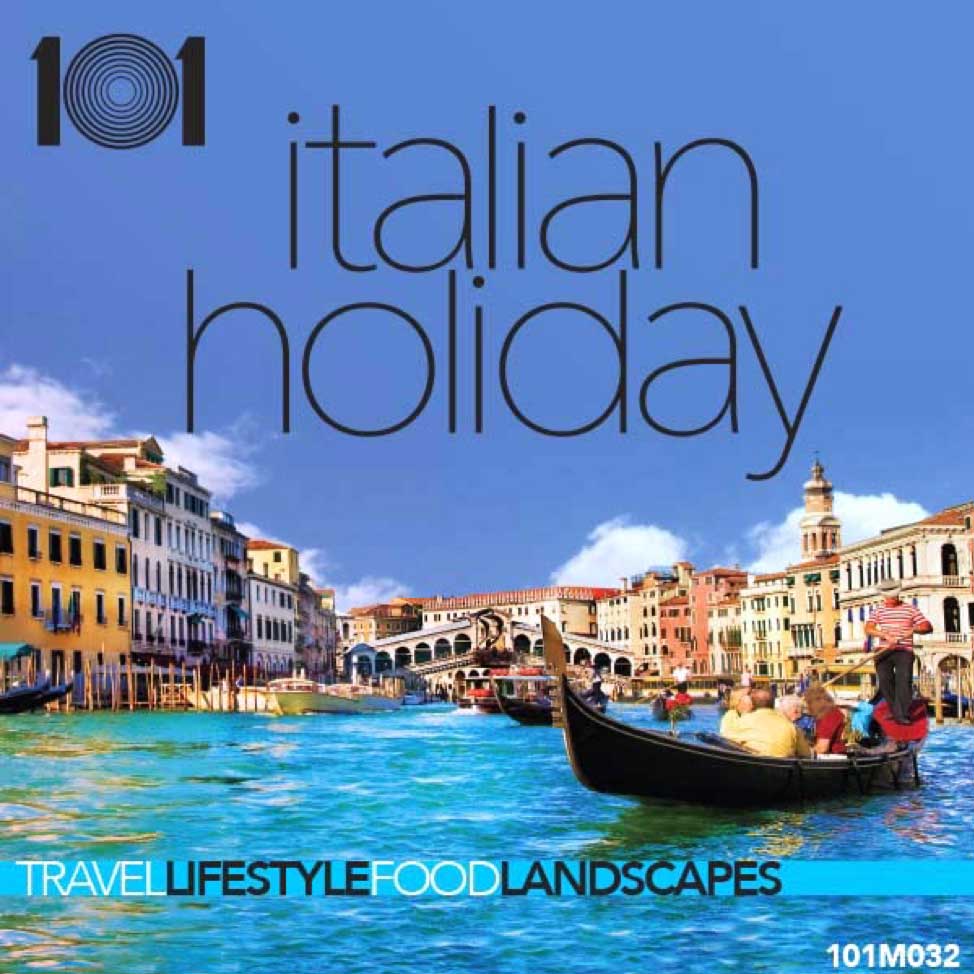

Another example of a release for 101 was a travelogue, food and lifestyle project, entitled Italian Holiday,

Once the album artwork is chosen, the 101 Music Pty Ltd design format is to utilize four keywords placed at the very bottom of the album cover as an aid for emotional identity. Every album release also includes a catalogue number in its company branded format.

In the metadata spreadsheet, the album description column always begins with the four chosen ‘magic’ keywords, then a descriptive sentence about the album itself, such as: 101M032 ITALIAN HOLIDAY – Travel, lifestyle, food, landscapes. Heartfelt, soulful and festive themes featuring beautiful mandolins and guitars of Italy.

Then, there’s a column in the spreadsheet notating the album keywords: Warm, beautiful, positive, upbeat, happy, jovial, loving, sincere, passionate, soulful, cheerful, heartfelt, delightful, friendly, joyful, festive, mandolins, guitars.

There is also a column notating the style and genre of the album: instrumental, Italian, Mediterranean, acoustic, folk, organic, travel, holiday, food, cooking, vacation, cultural, lifestyle, documentaries.

Further, for each track title the same applies: name of track title, version of track, description for track, keywords of track, genre, instruments used, tempo, key, track number on album release, composer name, affiliation to PRO, IPI number and finally an ISRC audio ID code.

Most of the above information is then embedded and resides alongside the actual digital audio file.

Here is a complete link to the 101 Music Pty Ltd music catalogue at the SourceAudio delivery site: https://101.audio/101-music-catalogue

‘Metadata and marketing is as important as the assets of exceptional quality music product – they both go hand in hand as one cannot work effectively or efficiently without the other’ (Phillips 2018).

101 Music Pty Ltd creates marketing concepts for its sub-publishers, but in a simplistic and cost effective form. The company provides small marketing morsels to utilize as tools to help promote the 101 Music catalogue in their respective territories, such as album advertising banners, a montage music sampler audio file highlighting roughly 30 seconds of each track contained on the album (roughly a 6-minute duration audio mp3 file teaser, which includes an excerpt of each track from the album in the precise running order), and ‘about the project’ highlights in a word document format for the sub-publishing agents to send to their clients. Everyone likes a story!

Here’s the advertising banner for ‘ITALIAN HOLIDAY’ (101M032),

I was honoured last year with a nomination by the prestigious Production Music Association ‘Mark Awards’ for ‘Italian Holiday’ for best jazz artist – as artist, guitarist, composer and producer.

Also in 2018, I was honoured by the Global Music Awards / USA with a silver medal award win for the same album release, ‘Italian Holiday’.

The money

And lastly, survival as a company is dependent upon financial returns, the money which hopefully is a result of the well-directed energy that the owner(s) of the company put into the business. Income vs out-goings can be challenging, especially if you wish to keep the standard of quality highly consistent.

It’s also very important to have good relationships with the best suited representative sub-publisher agent in each territory. Sometimes, depending on various circumstances, small independent agent sub-publishers may be better suited than the larger global companies to represent a small boutique library, especially in certain territories.

Generally, music that is organic and does not date will do best over time, as the long-tail effect kicks in. An example of this is the Chappell Recorded Music Library production music track mentioned earlier, ‘Puffin’ Billy’, composed by Edward White, that was used for the theme to Captain Kangaroo, an American children’s television series that ran from October 3, 1955 until December 8, 1984 – at the time making it the longest running nationally broadcast television program of its day.

Yes, there’s a saturation of music out there, but ‘Entrepreneurs should recognize and treat problems as opportunities. Entrepreneurs must create solutions to hurdles and road blocks that arise. They must think and operate in an unorthodox fashion – a little outside the box, with their shapes changing regularly’ (Phillips 2019).

In that, I lean toward the concept of diversity and creating music that has a strong cross section of style and possible usage, such as Lanza quotes, ‘the deWolfe (music library) has one Mozartian piano and orchestra number called Blue Porcelain that has played behind commercials for both a fancy European car and a feminine hygiene spray’ (Lanza 1995, p. 65).

‘The key to success is knowing and understanding your business as an ever-changing model’ (Phillips 2019).

Engaging the long-tail effect is an important business approach for me, by keeping organic as much as possible – this is the key I believe to a sustainable future within this industry.

________________________________________________________________________________

References

deWolfe Music 2019, (online) available at: https://www.dewolfemusic.com/rolloredirect.php?slug=Nitrate_To_Bitrate##1909

(Assessed 10 March 2019).

Johnson B 2019, ‘Think You Have A Hit? Make Sure It’s the First Song on Your Album’, by Lewis E 2019, Rolling Stone Magazine, USA, March 7, 2019, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/why-the-first-song-on-the-album-is-the-best-803283 (Accessed March 13, 2019).

Lanza J 1994, Elevator Music, p. 64 & 65, St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Lewis E 2019, ‘Think You Have A Hit? Make Sure It’s the First Song on Your Album’, Rolling Stone Magazine, USA, March 7, 2019, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/why-the-first-song-on-the-album-is-the-best-803283, (Accessed March 13, 2019).

Phillips A D 2018, Music & Media, Excelsia College, textbook for Masters of Music & Media subject, Sydney Australia.

Phillips A D 2018, ‘Music, Metadata, Marketing & Money’ (case study), Universal Business School Sydney (UBSS) – Centre for Entrepreneurship, Sydney Australia.

Phillips A D 2019, Guest speaker – Graduate Studies in Leadership, Graduate Certificate, Universal Business School of Sydney, Sydney Australia.

Production Music Association, 2019, online, https://pmamusic.com/retitling (Assessed March 11, 2019)

Rapee, E 1924, Motion Picture Moods for Pianists and Organists, the forward, G. Schirmer Inc., New York.

Saba, J 2017, (online) http://www.newscaststudio.com/2017/09/20/production-music-now-billion-dollar-industry, NewscastleStudio (trade publication for broadcast production), HD Media Ventures LLC company, September 20, 2017, USA (Assessed March 2, 2019).

Taylor, A 2017, (online) http://www.newscaststudio.com/2017/09/20/production-music-now-billion-dollar-industry, NewscastleStudio (trade publication for broadcast production), HD Media Ventures LLC company, September 20, 2017, USA (Assessed March 1, 2019).

The Media Management Group, 2015, The History of Production Music, (online) http://www.classicthemes.com/50sTVThemes/prodMusHistory.html (Assessed 4 March 2019).

Trunk, J 2005, The Music Library (Graphic Art and Sound), page 6, Fuel Publishing, London.

Yegezu H 2019, ‘Think You Have A Hit? Make Sure It’s the First Song on Your Album’, by Lewis E 2019, Rolling Stone Magazine, USA, March 7, 2019, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/why-the-first-song-on-the-album-is-the-best-803283 (Accessed March 13, 2019).

Information about the author, Art Phillips of 101 Music Pty Ltd and Art Phillips Music Design (online) http://www.101.audio http://www.artphillips.com

_________________________________________________________________________________

© 2019, Art Phillips, 101 Music Pty Ltd & Art Phillips Music Design, all rights reserved.

Please contact the copyright author and owner of this article (‘the paper’) for permission and licensing rights to publish and print, whether in physical print or on-line reproduction form.